I suffer from culture anxiety.

*

Born to a traditional mother with unyielding ties to her conservative Christian upbringing in small town, rural north-east Zimbabwe and a culturally liberal father tied more to his family than to the piece of land upon which his life was shaped, it now seems inevitable that I would develop two separate cultural identities, trying, but failing, to co-exist within one personality.

**

Almost every weekend, my brother and I were bundled up into the car, often fighting for the front seat & the subsequent dictatorship over the music choices for the trip, and together with the four families of my mother’s sisters made the two hour journey to her hometown. The trip was always a game of suspense until we passed the Macheke service station – would they let us stop and buy some soft drinks and warm pies or would we have to rush past in order to make it to church in time? Our church, a family establishment whose headship had passed down three generations and was molded in the image of the Anglican Church, held three services a day. We never made it for the Saturday afternoon service, despite aiming for it every weekend.

It was in this setting, in weekly intervals, that I learnt the traditions of my culture. For two days a week, I learnt the secrets of sisterhood and motherhood. Countless hours were spent gathered in communion with my mothers and their daughters, discussing what it means to be a Zimbabwean woman. In my culture, education is passed down informally, at meals, before bed, in impromptu gatherings. Nothing is written down – it doesn’t need to be; it is repeated often enough to become unquestionable fact over the length of your childhood.

Some lessons were invaluable, though unappreciated at the time. It is here that I learnt the art of inception, invented by wives & divulged by men. It is here that I discovered the inherent strength of African women, too often disguised as humility and misinterpreted as weakness. I lived the lessons of devoted motherhood. I witnessed the burden of the marriage vow being carried with dignity and bravery, despite the inevitable uneven load sharing. My mothers were Queens in the most noble sense of the word, defiantly regal in their cultural servitude to men, family and expectation.

Where I am from, a woman’s cultural identity is macroscopically stifling. When viewed through the superficial lens of simply interpreting actions without investigating the historical context, it is difficult to understand why modern African women would continue to embrace the paternalism of their ancestors. Why do we, successful and powerful in our professional lives, allow ourselves to submit to the role of unequal partner at home? Why does our opinion dictate the fate of entire organizations, and yet hold so little sway in our family affairs? Why do we work twelve-hour days, arriving home after our partners, only to rush into the kitchen to feed a “hungry and tired” husband? Why do we assume the role of single parent while a capable “partner” is at least physically, if not emotionally, present. Why must he assume that his only responsibility is financial and in some cases, not even that? Why must our worth be wrapped up in the success of our children and the cleanliness of our houses? Why is our name not always present on contracts or deeds or insurance policies? An African woman, like most women (albeit maybe more obviously) is treated as an accessory to the man – if he is a ruling King of his Kingdom, she is at best a figurehead Queen; a Prince Philip to his Queen Elizabeth.

***

Five days a week, I was raised on MTV and CNN, BET and Oprah. In school we read George Orwell, Shakespeare, Amy Tan, Arthur Miller. We studied the history of the world. I became tri-lingual by the time I was twelve and spoke four languages & read Latin by the time I was sixteen. I could read music, conversant in classical music and pop. I debated religion and politics, was an artist and a scientist, a musician and an athlete and I was never taught that being a woman would ever mean anything more than an additional piece of underwear. Five days a week, I was an equal to my brother in everything but age.

And as I began to think about the kind of woman that I wanted to be, the delicate tension between my two worlds began to expose itself. How could I be one without rejecting the other? My drive and unchecked dry humor would never have made a good traditional woman. I was too young to appreciate the benefit of personal censorship, a distinction I am yet to achieve. I was too independent to be humble. Too driven to be proudly second, even if second in name only. And if I chose to be the woman I was (mostly) raised to be, an unapologetic leader, equal to and surpassing my male peers, what would that mean?

Is my only choice to fully embrace or completely reject my culture, and with it my heritage? And in doing so, do I forfeit my authenticity when I refer to myself as Zimbabwean? And if not Zimbabwean, what? Where is my home?

****

I moved to Australia.

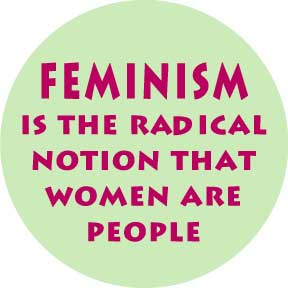

The decision was made because the opportunity was available, but the motivation was more personal than pursuing an education; it was an emotional and formative experiment to live life with one identity. Days into my new life, I felt myself free – I had finally found a cultural home. And along with the perceived bliss of immersion into western culture, the Internet became an important tool in informing and nurturing my identity. Because of my background, it was impossible then (and possibly even now) to view my burgeoning feminism as anything but a rebellion. While cognizant of the depth of history that has informed Shona culture, I am still unable to reconcile the idea that our traditions do not promote and cultivate female inferiority.

The dichotomy has been that while I have found a cultural home in which I join the majority opinion on the role of women in a society, I am in a racial minority. The irony being the subconscious (and thus manifest) belief by the racial majority that the colour of my skin points to a different cultural identity than their own. It has been a frustrating reality to embrace and an impossible identity crisis: does the freedom to believe that I am an equal member of society mean that I not only have to reject my cultural heritage, but also my racial identity? Is there a space in the world carved out for a woman like me and how do I get there?

My unanswered question remains: What does African feminism look like?

(While I’m looking for the answers, here’s someone who may be close to finding them)

Pingback: Top Ten Reasons Why I’m Still Single | There. I said it.